The new law makes Californians with criminal records “reasonably hopeful” that they will finally find housing

California Politics

Liam Dillon Ben PostonDec. 27, 2023

In 2021, four years after serving her last prison sentence and living in transitional housing in Riverside County, Erica Smith was ready for a permanent home.

She had saved enough to pay a deposit and first and last month’s rent for an apartment for her and her daughter. But after three months of searching, Smith ran out of money, having burned $10,000 on motel room stays. Shed never found a place to live.

Smith had a string of drug-related and theft convictions to her name. Numerous cities in Riverside had passed laws called crime-free housing, which aimed to prohibit landlords from renting to tenants with criminal histories.

It’s just terrible, said Smith, 54. Why can’t I offer me and my daughter a place to live?

Soon, Smith will have more options for housing, thanks to a new state law. Assembly Bill 1418, which takes effect Jan. 1, will prohibit local governments across California from enforcing crime-free housing policies.

Don’t do it alone

crime-free housing rules

not only

prevent landlords from renting to people with previous convictions, but

a lot of

So

a lot of

calling for the eviction of tenants based on arrests or contact with law enforcement authorities.

Dozens of cities and counties in California began implementing the laws during the wave of tough-on-crime measures in the 1990s, with local elected officials, police and prosecutors saying they helped keep neighborhoods safe.

But crime-free housing policies are increasingly criticized for being unfair, brutal and racially discriminatory. The blanket bans have left spouses and children of convicts without access to housing and victims of domestic violence have been forcibly evicted after police responded to their apartments.

Under AB 1418, local governments will no longer be able to evict landlords and evict tenants for alleged or prior criminal behavior. It does not prevent landlords from initiating nuisance-related evictions on their own initiative and from screening potential residents based on their criminal history.

More than a hundred cities adopted crime-free housing policies between 1995 and 2020, potentially covering 4.5 million renters, according to a new report from Rand Corp., a Santa Monica-based nonpartisan research institute.

The study found that, contrary to proponents’ claims, crime-free housing did not reduce crime rates.

Our overall finding is that crime-free housing policies are completely ineffective, says Max Griswold, assistant policy researcher at Rand and lead author of the study.

By means of

In contrast, the analysis found that the rules increased the eviction rate by about 20% on average, an effect that Griswold called unexpectedly large. The study found that cities with crime-free housing policies have a higher percentage of black residents than those without.

They create more segregation, Griswold said of the rules. Ultimately, that seems to be their goal.

Momentum to curb crime-free housing laws has increased in recent years.

A 2020 Times investigation found that the policy had disproportionately affected Black and Latino renters in California. Last year, the city of Hesperia and the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department agreed to pay $1 million to settle a civil rights lawsuit brought by the U.S. Department of Justice over allegations

are

The crime-free housing policy focused on removing black and Latino residents.

Citing The Times’ story and the Hesperia case, Assemblymember Tina McKinnor (D-Hawthorne) introduced AB 1418 in February. Shortly thereafter, California Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta issued formal guidance to local governments, urging them to reconsider their programs on racial justice grounds.

Doing that in the wake of the big Hesperia case made cities aware that the walls were closing in on them, says Anya Lawler, a lobbyist who

non-profit organizations the

California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation and

the

National Housing Law Project, two

non-profit organizations that are

main proponents of the bill.

Over the summer, California’s Reparations Task Force, in its recommendations for addressing the legacy of slavery and other more modern government-sanctioned policies that discriminate against Black residents, called for the repeal of crime-free housing laws

.

AB 1418 drew no formal opposition. It passed both houses of the Legislature without a dissenting vote in committee or on the floors of the General Assembly or Senate. Gov. Gavin Newsom signed AB 1418 in October.

Among those in favor of the new laws is the California Apartment Assn., the state’s largest landlord organization, which argued that local governments should not require landlords to foreclose or evict tenants.

As AB 1418 made its way through the Legislature, the two largest cities in the Inland Empire, Riverside and San Bernardino, agreed to repeal their crime-free housing laws. San Bernardino did this as part of a settlement challenging the policy in a case brought by legal aid groups, and joined by the offices of Bonta and Newsom, on behalf of low-income residents of the city.

At a hearing on the policy in August, Michael Griggs told San Bernardino City Council members he encountered hurdle after hurdle in finding housing. Griggs served six years in prison for robbery and assault

related tofor

a crime he committed as a teenager and was released in 2015.

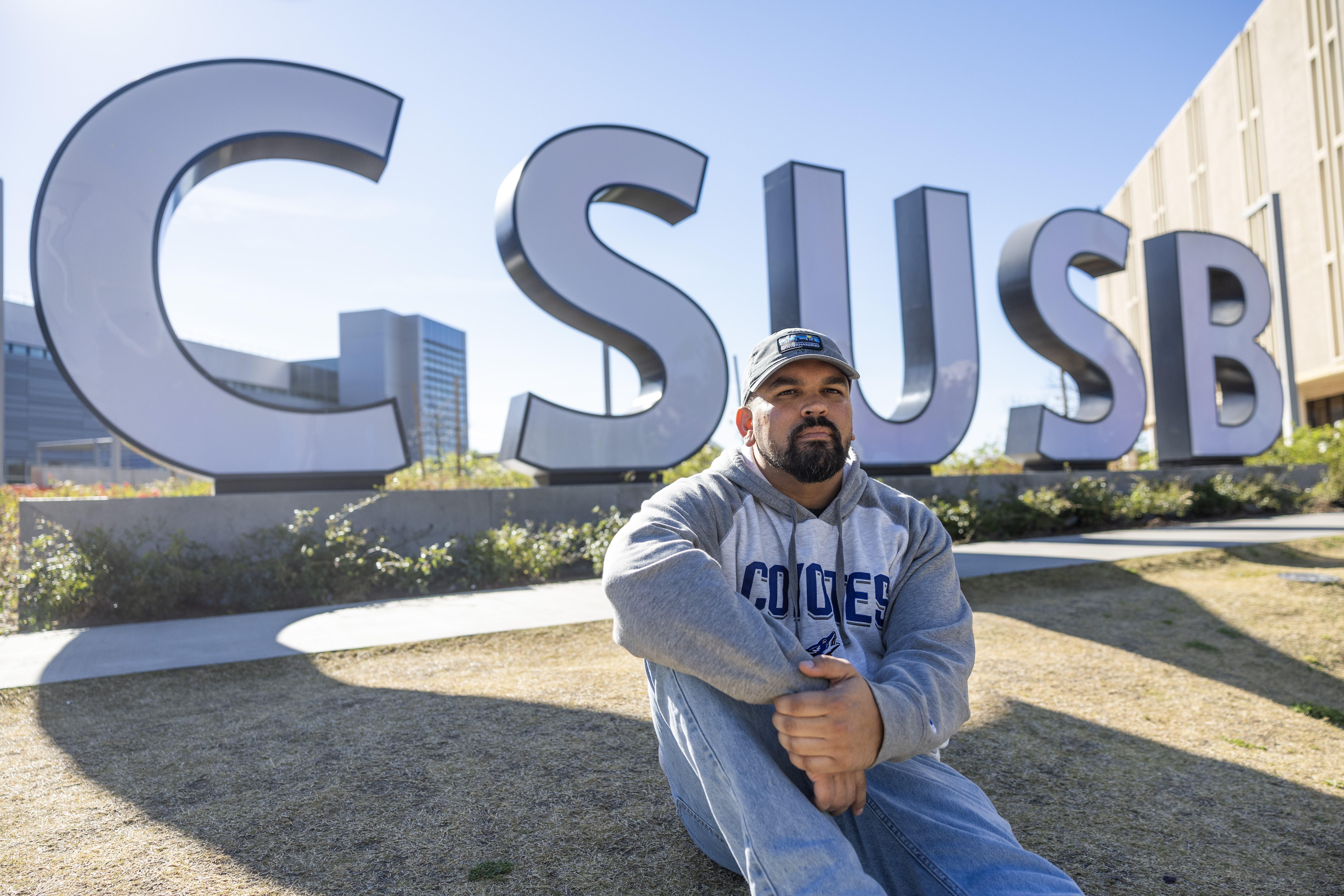

While in prison, Griggs began taking college classes. He earned a scholarship to Pitzer College and is now pursuing a master’s degree in social work at Cal State San Bernardino.

After entering graduate school in 2022, Griggs said, he spent six months looking for apartments in the Inland Empire, but landlords turned him down because of his criminal history. He said he

only

found a place in Highland, a city with a crime-free housing policy, about 10 miles from campus,

only

because the landlord’s background check did not extend to convictions that occurred more than seven years ago.

People want to get on with their lives, says Griggs, 34. How can they get on with their lives without having the first basic thing, which is housing, a safe place to live?

Griggs said he looks forward to AB 1418 erasing crime-free housing policies more broadly.

It’s hard work to do this at the city level, he said. I’m glad the state is taking action.

Local officials in Riverside and San Bernardino said they had already scaled back enforcement of crime-free housing programs. Ryan Railsback, a spokesperson for the Riverside city police, said the department stopped using an officer to enforce crime-free housing regulations in 2020 due to staffing shortages that arose during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In San Bernardino, the discussions are with the state

and local

levels

and local

about potential harm caused by crime-free housing rules, led city leaders to reconsider them afterward

three

on the books for decades, said city spokesman Jeff Kraus.

The nature of crime has changed, Kraus said. The laws have changed. People’s opinions have changed. It’s probably a good time to review them now.

For Smith, who remains homeless and lives in her car with her 12-year-old daughter, AB 1418 represents a new opportunity. She has worked with advocacy groups at the local and state level to protest crime-free housing policies, and recently received a federal Section 8 housing voucher that would subsidize her rent.

Smith has yet to find a landlord who will accept the voucher, but she expects that to change.

“I am excited and hopeful that because I have dutifully opposed these crime-free rules, part of the reward will be that housing will be available to us very soon,” Smith said.

Fernando Dowling is an author and political journalist who writes for 24 News Globe. He has a deep understanding of the political landscape and a passion for analyzing the latest political trends and news.